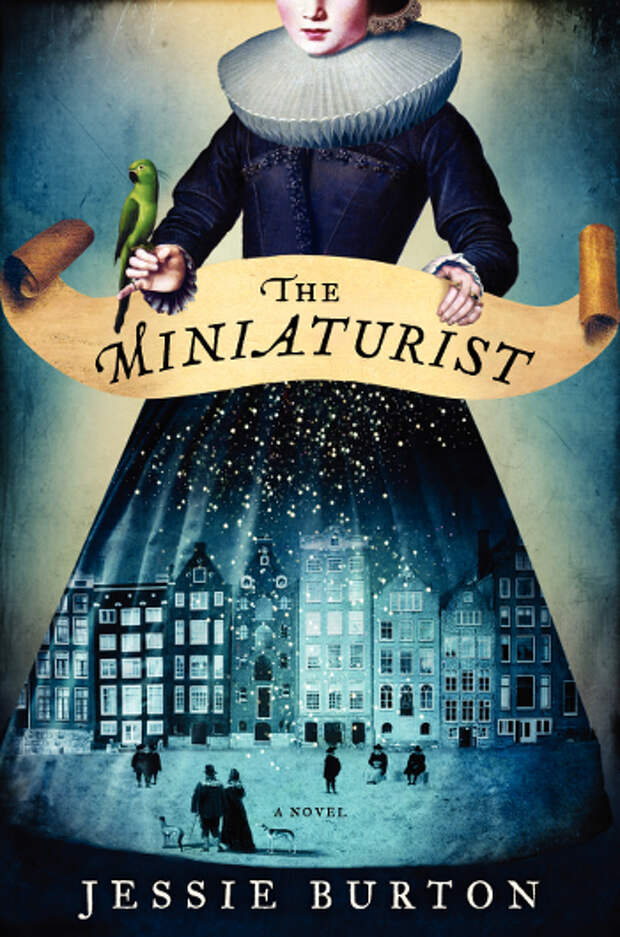

Out this month, "The Miniaturist" is the compelling and fascinating tale of a Dutch girl brought from her home in the countryside to Amsterdam, into the home of a rich merchant who's taken her as his bride.

What she finds inside the silent, often deeply creepy canal-side home she lives in astounds her, and sets off a chain of events that takes her on a journey through the worst, but also the best, of humanity. It's a stunning debut novel, and I was delighted to have a chance to talk with author Jessie Burton about the history behind the novel, her writing process, and more.Burton on writing in the past, without letting history constrain her:

"For me, 'The Miniaturist' is fiction before it is ‘historical’ fiction. The story (and the individuals within it) is king -- I did not want the novel to be a didactic display of how much historical accuracy I could cram in," she says, shying away from the "Historical Fiction" label. But while she focused on writing a plot-driven story that would connect readers with the characters, that doesn't mean she made up everything.

"'The Miniaturist' could not have existed," she notes, "if I had not undergone an immersive journey through late 17th century Amsterdam! The research was a complete pleasure and a constant wellspring of inspiration. Thankfully, the Dutch were inveterate self-documenters, so there was a wealth of iconography, wills, inventories, paintings, artefacts and recipe books left behind for me to investigate.

There was also the city of Amsterdam, which stands as a living monument to its own history. All information was easily accessed on the internet or from books. I only spent 10 days in the city itself, but spent 4 years writing the book."That said, she also encountered an interesting phenomenon when doing her research, particularly with respect to people of color in Amsterdam at the time. While she knew that the Dutch East India Company (VOC) traded in slaves, and some Black men and women arrived in Amsterdam even though the bulk of them were exported to the Caribbean, she found it difficult to track down documentation written by these members of Dutch society.

"I hope, had I had the time and money to travel to Amsterdam and rifle their archives, I may have found documentation pertaining to slaves, black servants and freed men in the city at the time, maybe in their own words. That is optimistic, but you never know," she says, explaining her frustration with the dearth of available documents.

This required thinking about the Dutch attitude towards the Black community in Amsterdam through the lens of tiny little pieces of history, sometimes found in surprising places, Burton explained: "During my research in Amsterdam, I noticed poignant reminders of the presence of African slaves around the city. Over the architraves of grand buildings I would see a black man or woman’s face, carved out of stone. I would also see them on coats of arms, or in the corners of paintings, dressed in the outfit of a page, or hired as a musician in a rich household. What I had to measure was the tone of this presentation. Generally, I felt it to be a fetish, another possession to put on show in the cabinet of curiosities."

Ultimately, when it came down to incorporating history into the text, Burton says that: "A historian once wrote that history was ‘a child’s box of letters, from which we may spell any word we please.’ He had a point. It’s a subjective thing, a curating game. Who wrote this history we take as set in stone? Which individual members of these past worlds have presented a collective story? You can amp the volume on something to push your own agenda, and lower it on another aspect. My approach was impressionistic. There are things in there I made up, but which people have assumed are historical exemplars. But I never said 'The Miniaturist' was anything else except a novel."

Sexuality in 17th century Amsterdam: Not always very fun!

That doesn't come as a surprise when one considers the complexity and context of the book. Without giving too much away, themes of gender and sexuality are as important as race, and Dutch records from the time are largely silent on the topic of personal experience. While documentation showed which crimes people were punished for and how, records from individuals affected by brutal laws against homosexuality are absent.

"One of the first things I came across when I began reading about the period," says Burton, "was the punishment exacted upon homosexual men if they were found guilty of the ‘crime’ of sodomy. Giant millstones would be placed around their necks and they would be pushed into the sea and drowned. It just stuck with me -- this brutality, this merciless baptism, all tied in with the Dutch relationship with the water that had given them so much bounty, but could overwhelm them. So from a civic, public point of view, you have utter condemnation."

She was curious about more than the "crime" itself and what happened to victims once caught by officials and condemned, often in sham trials. "But what of the sisters of these men, their mothers, their wives, even? Surely it would not be so simple for them -- would they not struggle with the love they held for their son, their brother, their husband, as much as they had to play their part in a tightly-knit society which will condemn them? The secret life, the compromises, the grey areas -- this is what I was interested in. Just because you’re from 1686, does not mean you will immediately call for the death of your beloved ‘deviant’. Some people would feel compelled to, of course. Others, maybe not."

This speaks to a larger desire on Burton's part to explore the good on the part of the characters in her book, challenging the common refrain that history is an excuse for bad behavior because "these were the norms of the time." Speaking about the treatment of the Black community in Amsterdam, for example, she says that: "I could not believe that every single white inhabitant of Amsterdam was happy to view these people as sub-human objects of fascination."

It's difficult to strike the balance between challenging history, and idealizing characters to the point that they start to feel like artificial dreams, rather than people who could have lived and interacted in that era. Burton treads that tightrope very well, ensuring that none of her characters are perfect and that many struggle with social norms of the time.

The cabinet house

At the center of the book lies a dollhouse, also known as a cabinet house -- it plays an intimate and critical role in the narrative almost from the very moment the heroine arrives in Amsterdam. I hadn't known anything about the cabinet house trend when I started reading, so I had to ask Burton about its role in Dutch society since it evoked so much curiosity for me, and it was such a provocative character in the novel.

"Dolls’ houses, or ‘cabinet houses’, were popular amongst the wealthy from the late 16th century. Often they were gifted to girls on the cusp of woman- and wife-hood, as educational tools on how to run a household. But they served another purpose, and that was one of display. Adult collectors would have these cabinets constructed, and they would place inside all their curiosities, their miniature valuables, the bits and bobs collected from their travels, or called across the oceans from the Far East."

This idea of the cabinet house goes far deeper than our modern dollhouse, turning it into a tool of ostentation, but also, to some extent, one of oppression, giving women a tiny, miniature world to play at being housewives in while men were responsible for the real world.

"They were status symbols, your perfect life on show, perhaps even a proto-Facebook," she says. "Women were often the collectors of miniatures, whilst their husbands managed the full-size curation of their homes -- make of that what you will. If you had a silk screen sent over from Java, you’d have a miniature one made too. It was a system of order, an opportunity to boast about how much money you had -- enough to spend on tiny fripperies that served no other purpose save that of ornamentation."

However, the dollhouses had a dark side, another streak that comes through clearly in the book and plays a very critical role in the tale. Even as the Amsterdam of the era was filled with ostentation, wealth, and displays of power, it was also filled with a deep sense of guilt and a desire to avoid appearing too smug.

"But there was a flipside to this ostentation and self-storytelling. Even though the most virulent, puritanical streak in Dutch society had really had its moment earlier in the century, there were still reactionary elements within the Dutch Provinces who feared such complacency and expenditure."

"The dread of dolls and idols was real," she says, speaking to several key events that happen in the book. "The authorities banned the sale of dolls in the 1620s, but also as late as 1670s, and gingerbread cut in the figures of humans was also banned. The celebratory aspects of life were always surging in Holland -- feasts, saints’ days, music and revels, but there was also a counterpoint -- remember where you came from, how your modesty has so far helped you to survive. Look forward, don’t gaze at your gingerbread navel."

This constant push-pull between two extremes, and the tensions that accompanied it, are a key part of the narrative for the reader, and the book at times whipsaws; a solemn gathering around a cone of sugar as people savor it but attempt to appear restrained about it, for example, is juxtaposed with a joyous festival or a sumptuous dinner.

Image: Wolf Marloh

Burton's writing secrets (or, how one author works)

To build up such a complicated, layered world, Burton had an interesting working style: "Generally when I write, I need silence, and being alone. I don’t need a view. A blank wall is better, because it’s all the mind’s eye. I can’t have the internet. I like candlelight, it’s calming. I like to write at night, because it feels (which I know is an illusion) that the world is quieted. My ideal hours would be 7pm to about 2am. The first, most important thing is to get the words out of your head and on to the page without worrying too much about their quality or where they’re coming from. You can worry about all that in the subsequent 16 edits you will have to undertake!"

She told me that she wrote the book in bits and pieces, pulling it slowly together into a full manuscript that went through a number of rounds of edits, including aggressive editing decisions. Over 20 characters were ultimately killed off, and she also eliminated storylines that didn't work within the context of the final piece. As she points out, the challenge of writing, and writing well, is often simply in relaxing and letting go while the words come out -- you can decide which words to use, and how, later.

As always, I had to ask Burton about her dessert preferences. Hailing from across the pond, though, she had an especially interesting take on the issue: "Cake. Cake, every time. When you say pie to me, all I can think of is English meat pies, which certainly have their moment on a wet and windy Sunday afternoon in November, but which have always been less appetising to me than a slab of coffee cake dotted through with walnuts, say. Or an Earl Grey chocolate torte. Or a lemon polenta cake. Or, or, or…"

I loved "The Miniaturist" for its depth, complexity, and driven, fascinating plot. I suspect many of you will too! Luckily for you, it's out now, so you can run to your closest bookstore and plunge right into it. (I recommend paying first.)

(All images courtesy Ecco Books.)