I was in line at the post office when it happened. The little girl in front of me was staring. She was maybe seven years old, and I sensed the exact moment that curiosity got the best of her.

She tugged on her mother’s hand, pointed to me and asked, “Mommy, what’s wrong with that lady’s face?” The mother turned around to look at me, hushed her daughter, and my heart sank into my stomach.

She was curious for good reason. My face, specifically the left side, is broken.

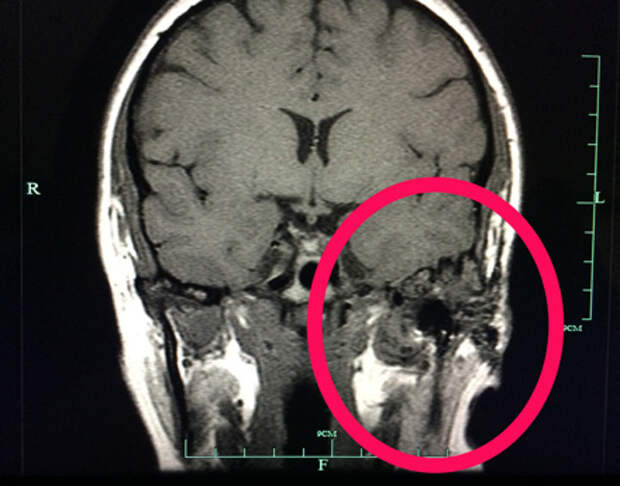

On June 30, 2008, at age 28, I went into an 11-hour surgery, my fourth that year, to remove an enormous tumor that had recurred in my jaw, precariously snaking around my carotid artery, creeping into my jaw bone and salivary glands, eating through my skull into my dura mater (the thing that covers the brain).

When I emerged a few days later from the ICU, I couldn’t feel the left side of my face, like I'd been given Novocaine that wouldn’t wear off. My doctors all told me to give it time. The surgery was massive. I’d get the feeling back eventually.

Doctors had first discovered my tumor about a year earlier when I woke up one morning and the bottom left side of my face was numb. I ran into the bathroom to look in the mirror, then, like any normal 27-year-old adult, I promptly called my mom to freak out because omgmyface.

I had been in pain for years and visited myriad doctors, only to be diagnosed with everything from teeth grinding to migraines to depression, and no, that last one never made any sense to me, either.

Every time a doctor would ask me what brought me to his/her office I’d respond the same way: “It feels like there’s something growing in my head and there’s not enough space for it.”

The tumor made its world debut on a dental X-ray right behind my jaw and looked like Slimer from Ghostbusters -- a shapeless, semi-translucent blob that was so large it fell off the monitor. My initial reaction was pure satisfaction -- I was right this whole time! There was something growing in my head! Then the satisfaction wore off and I realized that while I was right this whole time, there was literally something growing in my head.

It would take four months, three surgeries, and just about every pathology department in the New York tri-state area to diagnose me with Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis (PVNS), an extremely rare and equally aggressive tumor that forms in joints and destructs everything in its path as it grows. People usually get PVNS in the knee, ankle or elbow. Mine just so happened to make its home in my head, a far more treacherous and delicate stretch of the human body. Because “over-the-top” has pretty much been my M.O. since birth, this somehow made complete sense.

As my surgeon laid out the diagnosis I sat there quietly, not because I’m quiet by nature (please see: previously stated over-the-top M.O.), but because my jaw had been wired shut for several weeks so my bones could heal and my words sounded like something being squished through a juicer.

I had become very conscious of my illness at this point, having spent two weeks in quarantine at Columbia Presbyterian with MRSA (a very gross and kinda deadly infection), a pair of wire cutters always at my side in case I choked (just one of the hazards of jaw-wire-wizardry). I looked Frankenstein-y, my head partially shaved, gauze awkwardly Velcroed to cover the wounds and wires railroading my teeth, poking awkwardly out my mouth.

“Shwill id kim bashk? Ish id cansher?” I mumbled and sputtered and looked at my husband, Scott, who had become fluent in my wired lingo.

“She wants to know if it will come back. She wants to know if it’s cancer, “ he said, turning to me to confirm that he deciphered it correctly.

“No, no! This is done. Go live your life!” The doctor was so confident and nonchalant I actually believed him.

When the tumor recurred a few months later, I had just settled in at a plum new job and couldn’t believe my own good luck that I was able to rebound so quickly. I was chewing lunch when a familiar pain reappeared and the bottom dropped out from under my life.

It took a new team of about seven highly skilled surgeons to remove the tumor and repair as much of my face and skull as possible, followed by a five-week course of daily radiation a few months later to kill the disease and its chances of coming back. It took another five surgeries to successfully remove all the infections that erupted in my head and two more after that to repair a gaping hole in my skull the size of a small dinner plate. It took a little over four years to fully heal and regain my strength and about two years of therapy to stop the PTSD-based seizures I developed just for fun.

My head endured an Odyssean-level journey. It’s been cut, scarred, pulled, pushed, acupunctured, infected, drained and drugged. It was radiated to a crispy, painful burn that caused the skin to blister like the top of a pizza and swell so much that my normally round, brown eyes were reduced to thin, red slits. My face has seen some things. I should be singing its high praises for surviving what it did.

But I can’t, because I’m ashamed of my face. I’m grateful to be alive and well, but my face is frozen in a time and place that scares me to death. And I’m still in shock that it’s stuck like this forever.

The left side of my face droops with a paralysis that, over time, has broken my heart. I can handle the mental anguish and physical pain of a serious illness and all its accoutrements, but I can’t handle the fact that my smile is gone. I mourn it every single day.

Instead of a blemish or a bad hair day that can easily be covered with makeup or a kicky scarf, it’s an out-and-out deformity, and one that just so happens to be a testament to the scariest and sickest period of my life. In this age of Instagram and Facebook and the possibility of an upload around every corner, I live in absolute terror of someone candidly capturing it.

It’s not like I was a supermodel, but I was always so proud of my smile. It was big and warm and pretty, and it served as a perfectly fitting physical representation of my personality. I was proud of my lips and my teeth, straight from years of braces and white because of borderline-obsessive dental hygiene habits. It was, perhaps, the one part of my body I’d never, ever change.

Now my smile is wonky and unrecognizable. The left side of my face free-falls clumsily into my neck, while the muscles that remain contract uncontrollably into knots that I affectionately refer to as “face knuckles.” My lips pull up to the side and are usually peeling and cracked from lack of circulation, and they barely part enough to show my teeth, which I suppose is OK since they’ve become crooked and dull. The one-half of a smile that remains on my right side is perfectly intact, but it’s kind of a tease.

My illness is bookended by my first and last surgeries, which took place five years apart, almost to the day. In that time I missed out on a lot, from weddings to funerals to silly, fun nights out. I had to leave three different dream jobs with three great bosses. I’m pretty sure I lost any semblance of grace or dignity when I required the help of many just to pee.

But I survived a hellish trek for which there was no map or previously beaten path. I was lucky to be surrounded by supportive, loving and optimistic family and friends, the same ones who helped me pee, mind you. They helped carry the weight of everything I was going through, and they celebrate my good health now. While no one ever said I was close to death, there were times when I didn’t feel like I was too far from it. I have the wherewithal to recognize my good fortune.

But then there’s the seven-year-old at the post office, or the random stranger in the produce section of the grocery store who walked up to me while I was sniffing out cantaloupes to tell me, with a ridiculously inappropriate shit-eating grin, that I’ve “got the devil in my face.” And there’s me, when I unexpectedly catch a glimpse of myself and try not to cry because I’m in public and, maybe, it’s time to let it go.

I’m not sure when or if that will ever happen. I’m proud of what I’ve survived and I’m amazed at what the body can endure. I just long for the days when my smile made me happy instead of giving me pause to grieve.