Telling people that you research Facebook is a great way to collect complaints about Facebook. (Seriously, tell me your complaints; I legitimately find them fascinating -- I want to write a book about your complaints.) They generally break down into one of two categories:

- Other people are Doing It Wrong.

- Facebook is just bad for you, full stop.

The second complaint ranges in severity from a sense that we’d all have more free time and be happier if Facebook didn’t exist, to the conviction that we are at most a decade away from dating robots and the complete collapse of civilization.

As a sociologist of technology, I’m automatically suspicious of claims that Facebook is inherently different from other venues for interaction. The history of technological advances is also a history of technological panics:

- The radio will corrupt our youth.

- The telephone will create a nation of shut-ins.

- Facebook will destroy the true meaning of friendship (good thing we have nostalgia listicles to remind us about the Care Bears).

I was interested, but not surprised, to see that a recent study found that “social sharing,” defined as “communicating with others about significant emotional experiences” (Choi & Toma 2014: 530), played out similarly across various communication channels, from face-to-face to Facebook. Mina Choi and Catalina L. Toma at the University of Wisconsin-Madison recruited undergraduate students to complete daily diaries over a week-long period in which they recorded significant emotional experiences, whether and how they shared them, and their emotional states.

Their results largely replicated previous studies on social sharing via more “traditional” channels such as phone calls and face-to-face conversation (which, don’t get me wrong, is important work, given the general tendency to catastrophize digital media).

When people share positive experiences with others, they feel even better via a process called capitalization -- the people you tell react positively, you have a new, positive social interaction focused on the original good thing, you reinforce the memory of the good thing via that interaction, and you actively incorporate that good thing into the ongoing narrative of your life. It becomes more meaningful to you because you told other people about it.

However, when people share negative experiences, they tend to feel worse. Sharing leads to rumination where people might otherwise distracts themselves and may “make [the negative experience] more real,” as Toma suggested in UW-Madison’s press release.

Across channels, the exacerbating effect of sharing negative experiences was smaller for face-to-face sharing; the authors speculate that “the richness of face-to-face interaction provides more comfort for sharers.” Similarly, the study found that the positive effect of sharing positive experiences was greatest for face-to-face sharing.

I can see the editorials now: If we replace our entire social lives with Facebook, we will be less happy.

Of course that’s not how anyone uses Facebook.

Facebook does not supplant other forms of social interaction; it supplements them. Choi and Toma acknowledge that one weakness of their study is that, because most participants shared via multiple channels, it could not clearly separate the effects of those channels.

Someone sharing an experience face-to-face or via phone call may also post about it on Facebook, though only 8-10% of emotional experiences were shared on Facebook at all. Facebook, the authors argue, “is more of an everyday habitual communication channel, rather than a channel used for the sharing of special, meaningful events.”

Another limit of the study is highly salient: It restricted participants to the day on which the event occurred. It’s unsurprising that, within the same day, face-to-face interaction would be the most common venue for telling others about it.

Unless the event is extremely important or time-sensitive, it can probably wait awhile.

Furthermore, because we don’t replace all interaction with Facebook, there is a hierarchy of communication channels (and corresponding news recipients) to which we typically attend, and Facebook is usually at the bottom.

In my own research on Facebook use, I encountered frequent complaints about learning personal news from pseudo-public Facebook posts. One woman recounted learning about a friend’s engagement from a relationship status change in the News Feed rather than from an email or a private message, which she deemed more appropriate for the news and their relationship.

She took for granted that “close friends” should be told about an engagement before the much broader category of “Facebook friends,” and that they should therefore also be told via a more clearly targeted medium, such as email or phone. Learning about the engagement on Facebook essentially positioned her as “the last to know” (even if technically speaking, others read it later, or not at all).

Over the past few years I’ve observed a steady stream of Facebook pregnancy announcements. This particular type of news especially highlights the hierarchy of news recipients: pregnancy is a particular kind of news that is typically revealed to increasingly broad social circles as time passes.

On most pregnancy announcements, either a sonogram or a photo of the pregnant person is accompanied by a textual announcement of the pregnancy. These updates generally show high rates of interaction (which, thanks to Facebook’s algorithms, probably ensures that we keep seeing pregnancy announcements). Many other users “Like” them and a fairly high proportion also post congratulatory comments.

What I find most interesting, however, is the subset of people whose comments clearly display that the announcement is not news; that is, they are posting a public congratulations while simultaneously signaling that they are part of the poster’s inner circle, because they already knew.

While “Hooray! We can finally talk about it!” (yes, an actual comment I saw on a friend’s announcement) was noteworthy for its explicitness, its function was actually quite common.

Other happy events, while less prolonged than pregnancy, follow similar patterns of disclosure. In most cases, people are less likely to disclose an event on Facebook the day it happens the more important that it is. There is a set of recipients—family, close friends, etc.—that has to know before it can be “publicly” posted.

In order to really understand the role Facebook sharing plays in capitalization and subsequently enhanced positive emotional states, then, we need a wider timeframe than 24 hours. The good feelings produced by any one Facebook Like probably are fractional compared to a face-to-face conversation or phone call to a family member—but it’s not either/or. You can have both those things, plus 100+ Likes (and comments to boot).

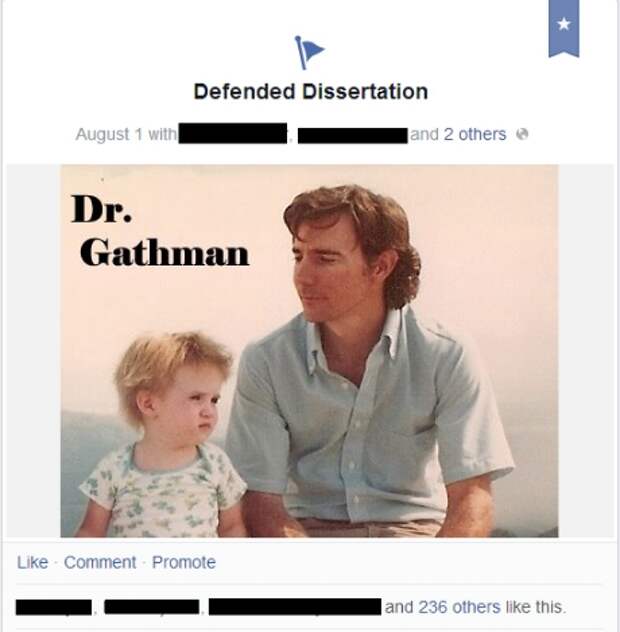

Furthermore, in at least one respect, one might expect Facebook to produce stronger results than mere face-to-face interaction: Facebook “Life Events” are specifically designed to emphasize particular events and embed them in our larger self-presentation: the chronologically ordered Timeline. What is Timeline, after all, if not the digitally documented ongoing narrative of one’s life?

When you view someone’s Timeline using the by-year navigation, Life Events are listed at the upper left. They also appear in the less frequently viewed “About” tab, which is itself a concentrated, if abbreviated, presentation of the self.

Following the general tendency to share negative experiences less publicly than positive ones, Life Events as defined by the Facebook interface are overwhelmingly positive. The only clearly negative ones are “Loss of a Loved One,” “End of a Relationship” (which might not even be that clear to anyone who’s ever attended a divorce party), and, somewhat mysteriously, “Broken Bone.”

While it’s true that Facebook does not provide a rich channel for comfort, it’s unlikely that anyone is using it as the first line of communication about deaths. Rather, not unlike a phone tree in years past, Facebook provides the bereaved with a fast, self-sustaining mode of news delivery. On Facebook, one can share news of a death once rather than countless times, generating countless emotional aftershocks.

Death, of course, is something of a special case in bad news. It’s governed by strong social norms of sharing: it’s permanent and it’s generally accepted that people should be informed about it quickly.

Most other types of bad news, conversely, are viewed as “need-to-know only.” People don’t generally want to incorporate them into their ongoing narrative—no one wants to be “the kind of person who loses her job,” etc.

Most bad news, then, is disclosed to others who are directly affected, either by the actual practical details (your roommate is going to want to know where the rent went) or because they are emotionally close and therefore “should know” about bad things that happen to you (whether you tell your parents or not, most people would say, tells us a lot about the kind of relationship you have with them; if you don’t tell your partner, there is obviously a problem).

Many people who don’t see Facebook as inherently bad still object to various behaviors they see as violating its (clearly still emergent) community norms. Occasionally, they mention others whose Facebook activity is a constant downer, usually because they feel insufficiently close to be receiving so many complaints.

More commonly, however, the behavior identified as common but objectionable is “vaguebooking”: the practice of posting cryptic updates that only allude to specific negative experiences or emotions.

Despite this widely negative assessment, however, vaguebooking remains common. That’s because it’s an adaptive practice: Vaguebooking is how people share bad news WITH Facebook without sharing bad news ON Facebook.

As Choi and Toma suggest in their results, sharing bad news with an insufficiently comforting recipient has major negative effects on our emotional state. Sharing bad news explicitly on Facebook runs the risk of a visible lack of response: Our bad experiences might be met with total indifference, which in turn would be preserved in the Facebook archive.

By alluding to our problems, but not stating them outright, we give our Facebook friends the opportunity to self-select as bad news recipients. Someone who has already made the effort to display that they care will probably react with appropriate sympathy to the news itself.

In fact, others may react by reaching out via more directed and/or immediate communication channels, such as text messages or phone calls, which Choi and Toma suggest less intensely amplify our existing negative emotions.

In these cases, the specific bad news may never make an appearance on Facebook at all, despite Facebook serving as an instrument for reaching out to those most likely to provide quality comfort.

How do you share your good and bad news on Facebook or other social media platforms? How many pregnancy announcements have you seen this year? And can somebody tell me why “Broken Bone” got its own Life Event category?