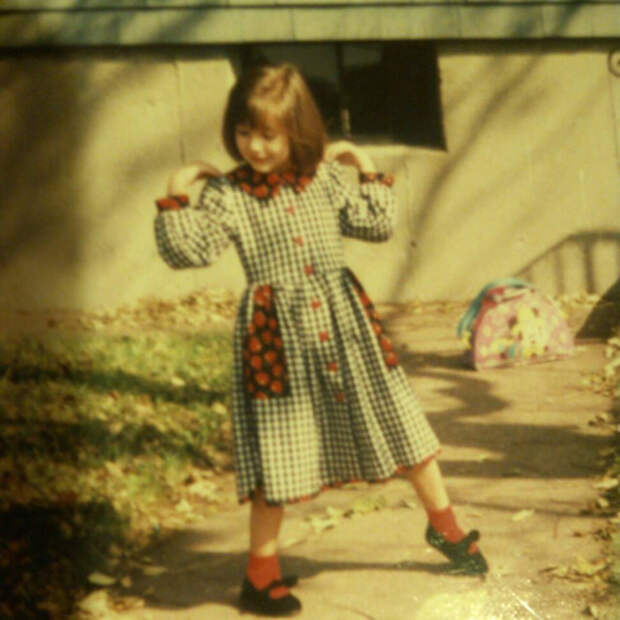

When I was a little girl, my greatest fear was that my mother would go to jail. These nightmares began when I was about four, perhaps five, and have lingered ever since, even though the fear has ultimately become a reality.

I still struggle with the words in my head, and hate to speak them: my mother, the inmate. My mother, the criminal. My mother, the user.

When you grow up with a parent who does nefarious things -– be it drugs, drinking and driving, shoplifting, what have you –- two belief systems become ingrained in your mind: One, that what your parent is doing is wrong and that you shouldn’t do it, and two, that you and need to say and do whatever possible so that your parent doesn’t get caught. Whether or not you partake in the activities almost becomes a moot point –- through a child’s eyes, you become a sort of accomplice, and you feel the anxiety of their risks with none of their thrill. It’s surreal, and bizarre, as though you’re falling off a cliff without ever having jumped.

Though I worried extensively about my mother, we were never very close. Emotionally, there were yards of distance between us, and many things we never talked about. As an only child, I was always desperate for my mother, but our strongest bond was always the one which surrounded her secrets: pill abuse, drunken stupors, baggies and burnt spoons. I was lucky enough to be raised primarily by my grandmother, whom I love deeply, but still, my mother was always my greatest worry and I protected her relentlessly.

Until one day, I didn’t.

I moved to New York after I graduated from college, and made the journey from Boston on a Megabus, alone, with one suitcase and one backpack. It was crazy, absolutely, but I was determined to be independent and, truth be told, I knew that if I were to cut ties with my mother, she couldn’t know where I lived, else I wouldn’t ever feel safe. Her tempers were insurmountable, her moods, unpredictable. Even at 22, I was terrified of her.

Several months after I moved to the city, I changed my phone number and made a new email address. I meticulously blocked all of my immediate and distant family members on social media. When I planned my wedding, I sent no invitations to aunts, uncles, cousins, or my beloved grandmother. I feared my mother too much, and I feared my own lack of resolve; I feared that if I gave in just a little, I could never remove her from my life again. I cried most nights, overcome by guilt and panic. I told myself that while not everyone would see my choice as the right choice that it was the right choice for me, and that was the best I could do.

I knew my mother was homophobic, as she had accused me of being a lesbian on numerous occasions, and threatened to disown me, or worse, kill me. But my sexual orientation was only part of the reason I cut ties, though it is the one I am most comfortable sharing when people do ask about my estrangement. Years of emotional and psychological abuse still linger, and I knew that to become a healthy person myself, I could not have my mother in my life: even so much as a text message sent me into a dark place, and I worried for my ability to have healthy relationships and maintain a steady job with her influence in my life.

Still, I could not let go of her. In some ways, I feel like I am talking about an obsession or an addiction –- I spent so much of my life crying over, obsessing about, and protecting my mother, I felt both freedom and ultimate despair upon my sudden and complete cut from her. It was my own choice, but still, I felt panicked.

I took to Googling her every day, then every week, then sometimes I stopped for months at a time. One afternoon, my wife and I were doing our searches, and she pointed to an article I hadn’t seen before. It was from a small newspaper based in my hometown, and detailed a horrific account of the crime my mother was charged with.

I read the words with a mixture of shock and disbelief. Hours later, when I had stopped crying, my wife asked me if I was surprised at what my mother was accused of. I both was and wasn’t. For much of my life, I believed in the good in her, and convinced myself her abusive nature, threatening words, and physical violence were solely a result of her drug use. But in my two years of separation from her, my vision of her is changing, and I know that her wrongdoings were of her own making, and no one forced her hand.

I found her name on the inmate list of a correctional facility in my home state, and through updates of their records I gathered an estimation of the time she had served. Her inmate number was listed and I often contemplated writing to her, but I never did. What would be appropriate? A birthday card? A Mother’s Day care package? Can you send flowers to a jail cell?

But then I reread her crimes in my mind’s eye, and the memories come back, and I know that I am not a little girl anymore. She has no power over me, and I am no longer fighting for her love.

When people ask about my relationship with my family, I always struggle with an answer which is both appropriate and honest. Estranged is the best way I can describe it, though I have recently gotten into contact with an aunt and uncle, whom I’ve visited and email with occasionally. Still, when I think of my family, I first think of my wife and our cat.

Sometimes I am overcome with an intense sensation of paranoia: Will my mother track me down? Will she find my photographs online and stalk me and my wife? Will she be angry? Will she hate me? Will she hurt me? But I am not a little girl anymore and I am not at her mercy. I am my own person and I cannot fall back into her familiar, albeit frightening, arms any longer.

Life is fluid, and nothing is absolute, but we make the choices we make and it is ultimately up to us to stay strong to the lives we want for ourselves. I choose happiness, health, and safety, though not without guilt and remorse for the relationship with my mother that might have been.