When I was an 8-year-old jumpy and artistic little Bulgarian, my opera singer neighbour suggested I take up classical ballet as a hobby. “For better posture and a more refined cultural outlook on life,” she preached.

At the time I was dancing for fun to current pop hits in a local group and had already fallen in love with the limelight, not to mention the coolness that came with being in the go-to children’s dance troupe for TV shows and concerts (to this day I’m convinced that if my TV career had started in the US instead of in Eastern Europe, I could’ve been a Disney child star). In love with dance and not yet realizing the difference between “dancing for fun” and studying classical ballet, I started attending classes twice a week. Two years later, I found myself at the entrance exam of the National School of Dance Art.

My weight had been a topic of discussion since day one in the ballet studio. It was made very clear to me that my already very distinctly feminine hip-to-waist ratio was not exactly desirable for a ballerina and the cloud of horror that was my impending puberty was soon casting its long shadow. But the roller coaster of verbal abuse and the gradual destruction of every ounce of self-confidence I’ve ever had were just about to begin.

It was at the entrance exam where an examiner pinched my butt, pointing it out to the rest of the sour-looking committee and made a snarky comment about its ballet potential.

Nevertheless, I got accepted -- last on the list, with the lowest score above the required minimum and a taste of what was to come in the next 9 years of professional ballet training. How and why I got accepted is still beyond me and I often wonder how my life and personality would’ve turned out if my score had been a tenth and a bit lower.

The weighing started almost immediately and with it came a sneaking suspicion that giving too much meaning to the number on the scales is not right. At our very first end-of-the-year exam, I was told that my grade had been lowered due to the size of my butt. I was 10.

The next year I grew up in height very abruptly (and haven’t grown that much more since) and had severe knee problems accompanied with excruciating pain and the possibility of dance-ending and walking-impairing injury. I might’ve needed help walking between the ballet studios, but once I was in one I was loved by the teachers -– I had grown so fast that the kilos hadn’t had the chance to catch up. I was so ecstatic to be receiving the attention and the stage time that came with being judged “not that fat anymore” that I kept pushing myself through tears and migraine-inducing pain.

But after the following summer was over and my calcium was back to normal, so was my body’s shape. Back were also the physically impossible tasks and puzzling questions from my instructors, such as “Why is it so hard to just lose 3 kilos from your butt? You’re not even trying, are you?”

During the 9 years in ballet school, we would sometimes be taken to the nurse’s office, put on the scales and given a weight loss ultimatum for the next two weeks or a month. The poor nurse always tried to soften the blow at the initial weigh-in by giving a lower number to the teacher who would write it down in our official grade report cards (straight As in everything from math to biology but always 2 or 3 kilos to lose from ballet classes) and add the future expected number.

Unfortunately, by the follow-up weigh-in the nurse would often forget the initial made-up number and I’d risk ending up at the same or, worse, higher weight. Those second trips to the scales were hilariously tragic crash lessons in pantomime between the nurse and me, hopelessly trying to indicate the need for a lower number than the one she had already half-said.

The weigh-ins always gave surprising and confusing results. One of my classmates, a girl with perfect ballet physique, narrow hips, lean legs and long arms would always weigh more than me and, as a result, my suspicion about the meaning of The Number only deepened.

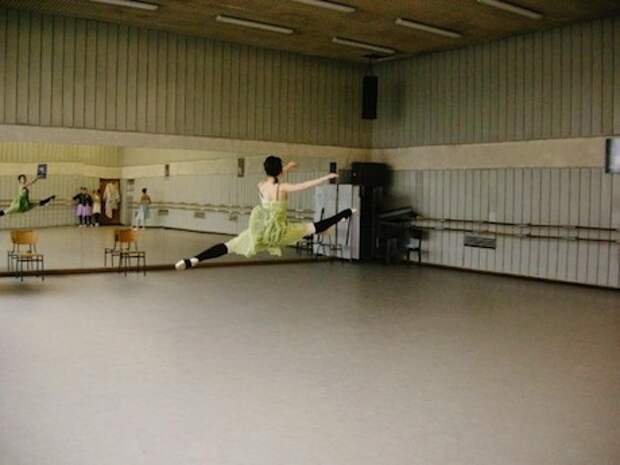

Days, weeks and months passed in relentless training -- 5 or 6 days a week, anywhere from 3 to 6-7 hours a day -- and my lower body would refuse to obtain the ever-so-fawned upon “dancer’s legs,” instead leaving me with big and sharply outlined muscles, more reminiscent of a soccer player’s than a delicate swan’s. The more muscle I’d put on, the bigger my Number would get and my nature-given combination of wide hips and a small waist would make my un-ballet-like shape even more noticeable and prone to insults.

In the peak of puberty, I gained a lot of weight in the course of just 3 months. Starting the new school year with additional 8 kilos on top of an already unacceptable figure meant a long period of being completely ignored in the studio or receiving only a fleeting mention when a chance to be bullied presented itself. To this day, my favourite line from that time is: “You’re so fat that right now you’re dancing in this studio but your ass is dancing in the studio next door!” After finding out that I was having a hormonal problem, I decided to lose the weight with the help of a nutritionist. But losing weight the right and healthy way takes time and when it came to shedding kilos, taking your time wasn’t applauded.

In the last two years of my training, I was looking forward to the end of this madness and knew I would be quitting for good. It was clear to me that I was never going to be a ballerina and, contrary to common sense and professional ethics, it was me who had to take the responsibility to admit and decide it. Why they kept me all that time despite my unacceptable body is still a mystery to me.

The year after I quit. I lost a significant amount of weight. Finally, I found myself at the perfect Number for ballet. When I randomly met a former teacher she noticed my newly protruding bones and after mentally measuring me up and down said: “Well, if only you had been that thin in school!”

“Well, if only you hadn’t been a bully,” I thought.

Soon after, my weight was back to the human average, my butt was asking for a special jean cut at the store and my mind was struggling to accept my weight’s normalcy, insisting that it was most definitely in the “chubby” diapason. Yet slowly but steadily, I began consciously rewiring my brain and trying to distance my own opinion of my body from that of my former teachers. I was surprised to find out that I was totally okay with it.

Five years after the last time I put on pointe shoes and went on stage, I have stopped weighing myself and caring about the Number. Today it seems ridiculous to me that when I was an insanely strong and athletic person, I’d feel so bad about my body and I now realize that weight is something very easily taken out of context.

I’m very aware that when I tell people I was a ballerina they hesitantly look down to my hips and legs before saying “Oh, really…” and I’m no longer embarrassed by it. After over a decade of working with my body, I have finally learned to listen to it, to experience it and to make my weight loss decisions based on how comfortable I feel in it. I haven’t weighed myself in a year and I’m not even remotely curious in a mere number.